"The Yankees Have Been Here!":

The Story of Brig. Gen. Edward E. Potter's Raid

on Greenville, Tarboro, and Rocky Mount,

July 19-23, 1863

DAVID A. NORRIS

"I am as busy as a bee preparing for

the coming of the Yankees. I believe they will certainly be

here this Fall, probably this summer. . . . And I am attempting to so arrange matters that the

family can all leave in case of an emergency. Mother is very nervous about affairs and Alice is

terribly frightened--all her boasted courage has oozed out of her fingers' ends." Prominent North

Carolina jurist and superior court judge George Howard, who was in Tarboro attending to his

family's properties, hastily wrote these lines to his wife in July 1863.1 Union forces had held

Plymouth, Washington, and New Bern since the spring of 1862, and from these strong points they

periodically launched raids deep into the interior of North Carolina's Coastal Plain. Gov.

Zebulon B. Vance warned the Confederate secretary of war that "the Roanoke, the Tar, and the

Neuse, embracing the richest corngrowing regions of the state, upon which the army of

Gen.[Robert E.] Lee has been subsisting for months" were inadequately protected.2 Much of

Virginia had been ravaged by two years of war, and her farms could not supply enough food to

sustain General Lee's troops. The corn, wheat, and pork of eastern North Carolina had become

important to the Confederate war effort. And, although North Carolina was providing the

Confederacy with more troops than any other state, the majority of Tar Heel soldiers were in

Virginia or South Carolina. As one newspaperman wrote, North Carolina was not left with

enough troops to "protect a potato patch. . . . [Our state is not receiving justice."]3

Like Judge Howard, Brig. Gen. W. H. C. Whiting and his subordinate, Brig. Gen. James G. Martin

were also concerned about Union attacks. Whiting was the Confederate commander of both the

Department of North Carolina and the District of the Cape Fear.4 He focused

1. George Howard to his wife, July 14, 1863, George Howard Papers, East Carolina Manuscript

Collection, East Carolina University Library, Greenville, N.C.

2. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union

and Confederate Armies, Ser. I, Vol. 18, pages 1027-1028 [hereafter cited

as Official Records (Army)].

3. Wilmington Journal, July 30, 1863.

4. The boundaries and commanders of the Confederate militarty departments and districts

changed with aggravating frequency. In July 1863 the Confederate military's Department

of North Carolina consisted of two districts:

|

| Page 2

his attention on defending Wilmington, which had become the South's busiest port as a result

of the Union navy's blockade of Confederate shipping on the East Coast. Martin, the Confederate

commander of the District of North Carolina, was responsible for protecting the vital

Wilmington and Weldon Railroad, which supplied General Lee's army in Virginia with North

Carolina foodstuffs and a variety of war materiel including weapons, ammunition, and

medicine-that had been brought into Wilmington through the Union blockade. Cutting the

Wilmington and Weldon Railroad was a major objective of the Union army in North Carolina.

Judge Howard and his Tarboro neighbors were justified in their worst expectations of a Union

raid. News of the disastrous Confederate losses at Vicksburg and Gettysburg in early July was

spreading, and North Carolinians feared that the Federal army would immediately seek to

exploit its advantage by striking into the heart of the state from its stronghold in the east.

Much of the eastern part of the state was either under Union control or within the range of

Union raiders. The few regiments of Confederate troops in the region were too widely scattered

to provide a proper defense against the sudden and swift attacks by Union troops.

Historians have underestimated the significant impact that such raids had on the conduct and

outcome of the Civil War. Although the overall physical damage of the attacks to the

Confederate war effort was minimal, they nevertheless had a profound tactical and psychological

effect that weakened the Confederacy's ability to wage war. In 1863 Federal forays into the

interior of North Carolina created panic, even among the state's leaders, who pleaded with the

War Department in Richmond for protection. "Let me beg you to send every available man, as I

am sure the crisis is upon us in North Carolina," Governor Vance wrote Sec. of War James A.

Seddon in anticipation of a raid in January.5 That same fear depleted the morale of the state's

citizens and undermined their support for a war of Southern independence. Responding to the

threat of yet another raid, Vance on April 23 wrote to Gen. Daniel H. Hill, Confederate

commander in eastern North Carolina, that "I have addressed a note to the City Editors urging

them to avoid exciting any panic among the people.. ,"6 The panic among white North

Carolinians was enhanced by the large number of potentially vindictive slaves liberated by the

Yankee raiders. The Federal attacks also weakened the Confederate war effort by drawing troops

away from battlefields and other vital areas in order to defend North Carolina's towns, railroads,

and supply centers. "We are straining to send forces to you," Seddon replied to one of Vance's

cries for help.7 From Goldsboro on another occasion General Hill informed Vance

that "as we have a new

the District of the Cape Fear, which included Wilmington, Fort Fisher, and surrounding areas; and

the District of North Carolina, which administered all of the state beyond the Cape Fear region.

5. Zebulon B. Vance to James A. Seddon, January 20, 1863, in Frontis W. Johnston and Joe A.

Mobley, eds., The Papers of Zebulon Baird Vance, 2 vols. to date (Raleigh: Division of Archives

and History, Department of Cultural Resources, 1963-), 2:20.

6. Zebulon B. Vance to Daniel H. Hill, April 23, 1863, in Johnston and Mobley, Papers of Vance,

2:129. Morale and support for the war were further undermined by such problems as conscription,

desertion, impressment, tax-in-kind, speculation, and shortages. Ultimately, many North

Carolinians began supporting a peace movement led by Raleigh editor and politician William W.

Holden. For an account of that movement, see William C. Harris, William Woods Holden:

Fireball of North Carolina Politics, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987),

127-136.

7. James A. Seddon to Zebulon B. Vance, January 6, 1863, in Johnston and Mobley, Papers of

Vance, 2:7.

|

| Page 3

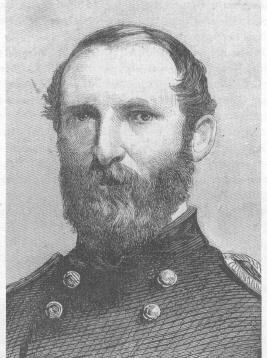

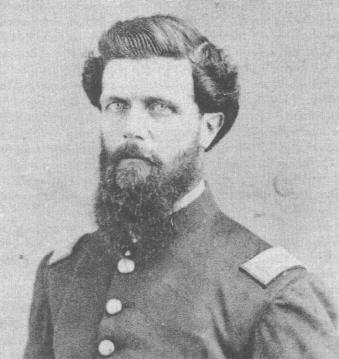

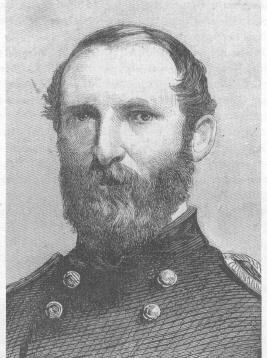

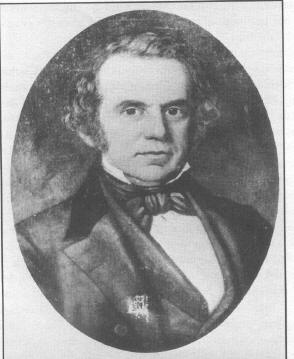

Maj. Gen. John Gray Foster served as commander of the Federal Department of North Carolina (December 24, 1862-July

11, 1863) and its successor, the Federal Department of Virginia and North Carolina (July 11-November 11, 1863).

Encouraged by the outcome of a small Union raid on Kenansville and Warsaw in early July 1863, Foster planned the

more extensive expedition that became known as Potter's Raid. Photograph of engraving from the State Archives,

Division of Archives and History, Raleigh.

excitement about immense [Union] reinforcement at Newberne, I am afraid to leave here."8 An

examination of the planning, execution, and aftermath of Brig. Gen. Edward E. Potter's raid on

Greenville, Rocky Mount, and Tarboro in late July 1863 demonstrates the impact and

importance of the raids that caused so much concern among Confederate and state leaders.

As of July 19, 1863, the dreaded Yankee troops had not been seen near Tarboro. Judge Howard

wrote, "everything is more quiet here now than we have been for the past two weeks--less

apprehension felt of a Yankee raid. We all feel relieved."9 He did not know that as he penned

that letter to his wife a Union general and eight hundred cavalrymen were within a few miles of

Tarboro.

Maj. Gen. John Gray Foster commanded the Eighteenth Army Corps, a force of 9,600 Union

soldiers "present for duty" of whom about 7,000 were based in New Bern.10 Smaller

8. Daniel H. Hill to Zebulon B. Vance, March 3, 1863, in Johnston and Mobley, Papers of Vance,

2:77.

9. George Howard to his wife, July 19, 1863, G. Howard Papers.

10. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 3), page 733.

|

| Page 4

garrisons held Washington, Plymouth, Beaufort, and Morehead City. The Union forces generally

stayed close to their fortified towns, while making scouting and foraging expeditions and an

occasional cavalry raid.

Early in July 1863 General Foster had ordered his largest cavalry raid to date. Six

hundred forty

men of the Third New York Cavalry, commanded by Lt. Col. George Lewis, rode to Kenansville,

the site of a Confederate arms plant, and Warsaw, a stop on the Wilmington and Weldon

Railroad. The raid targeted places of minor importance to the Confederacy. General Foster

planned a more extensive raid that would "traverse a circuit of 200 miles, and . . . do much

damage."11 The targets of this new raid were Tarboro and Rocky Mount. Tarboro was an

important regional river port with warehouses that held considerable stores of Confederate

supplies. Perhaps most worrisome to the Union was an improvised shipyard across the river from

the town, where the Confederate navy was building an ironclad gunboat similar to the famous

CSS Virginia.

Rocky Mount was even more important to the Confederacy. The largest cotton mill in North

Carolina, the Rocky Mount Mills, turned out great amounts of cloth for Confederate uniforms.

Also, near the station was a long bridge over which the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad

crossed the Tar River. Destroying this bridge would seriously disrupt the South's already

tottering rail system and prevent General Lee's army from receiving desperately needed supplies

following the Battle of Gettysburg.

Perhaps disappointed with Lieutenant Colonel Lewis's performance on the Kenansville-Warsaw

expedition, General Foster appointed his chief of staff, Brig. Gen. Edward E. Potter, to lead the

new raid.12Potter assembled a mixed force of cavalry and artillery for the expedition. A large

number of his men were from New York cavalry regiments--the entire Third Regiment,

Companies A, B, and F of the Twelfth Regiment, and two companies of the new Twenty-third

Regiment. Also included among these cavalry companies was Company L of the First North

Carolina Volunteers. Potter divided the cavalry into three battalions of six companies each.

Maj.

George W. Cole and Maj. Fenis Jacobs Jr. each commanded six companies of the Third New

York Cavalry; Maj. Floyd Clarkson was in charge of the remaining six companies. The artillery

contingent consisted of a two-gun section of the "Flying Battery" of the Third New York

Cavalry, under command of Lt. James Allis, and another two-gun section from Battery H of the

Third New York Light Artillery, under command of Lt. John D. Clark.13

To create a diversion to cover the Union plans, General Foster sent a brigade of infantry under

Brig. Gen. James Jourdan ahead of the cavalry. On Friday, July 17, Jourdan and his men

marched north toward Swift Creek Village (modern-day Vanceboro), where they captured

11. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), pages 858-867,

(Part 3), page 723.

12. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 964.

Edward E. Potter was born

in New York City in 1823. He studied law, went to California during the Gold Rush, and

then returned to his native state for a life of farming. He enlisted as a captain in the

Union Army early in 1862 and rose to the rank of brigadier general by the end of the year.

Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Blue: Lives of the Federal Commanders

(Baton Rouge: University of Louisiana Press, 1964), 380.

13. Potter's four cannon were twelve pounder mountain howitzers that were small enough

to be taken apart and carried in pieces by pack animals. These cannon were well suited for

fast-moving cavalry detachments -- they were light enough to haul through roadless woods

or along swampy area where heavier guns would become bogged down. Jack Coggins, Arms

and Equipment of the Civil War(1960; reprint, Wilmington, N.C.; Broadfoot Publishing

Company, 1990), 75.

|

| Page 5

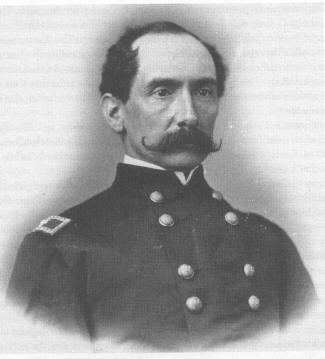

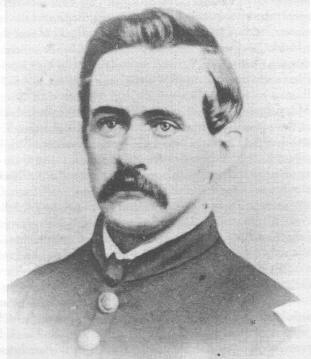

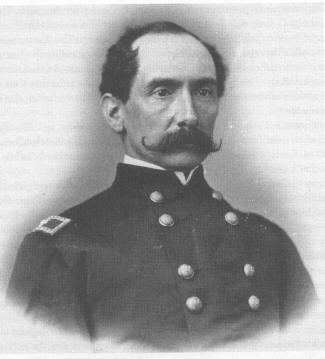

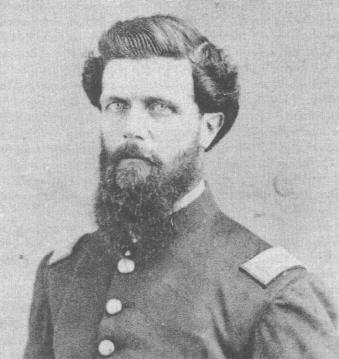

Brig. Gen. Edward E. Potter was responsible for executing General Foster's

planned raid on Greenville, Rocky Mount, and Tarboro. A native of New York, Potter enlisted

as a captain (February 3, 1862), was appointed lieutenant colonel (October 1, 1862), and

was then raised to brigadier general (November 29, 1862). Photograph from Massachusetts

Commandery Collection, Militaty Order of the Loyal Legion United States (MOLLUS),

U.S. Army Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, Pa.

one soldier, several carts, some livestock, and a few guns. The Yankee infantry then settled in to

wait for Potter's cavalry.'14

The cavalry expedition began slowly: the troops were ordered to prepare to leave New Bern on

July 17, but they did not cross the Neuse River until the next morning. One soldier noted that

they loaded their horses aboard flatboats at 6:00 A.M. on Saturday, July 18, but it was noon

before they stepped off on the opposite bank.15 The men landed near Fort Anderson,

a Union outpost on the north bank of the river across from New Bern. From there they rode

toward Swift Creek Village, where they joined Jourdan and his men that

14. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), pages 967-968.

15. Herbert Arthur Cooley to his father, July 26, 1863, Herbert A. Cooley Papers

(typescripts), Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina Library,

Chapel Hill; Gleason Wellington to his mother, September 6, 1863, Gleason Wellington

Correspondence, Oswego County Historical Society, Oswego, N.Y.

|

| Page 6

evening. The cavalrymen posted guards and established camp for the night. That would be the

last good night's sleep that Potter's men would receive for several days.16

At dawn on Sunday, July 19, the Union troops broke camp. The destination was at first a

"mystery to all,"17 but the men soon learned that they were riding to Greenville,

about twenty-five miles to the north. As the cavalry left, General Jourdan's infantrymen

remained at Swift Creek Village with orders to return to New Bern the next day. One of

Jourdan's men wrote ruefully of the march to and from Swift Creek, "I never suffered so

mutch from the heat in my life."18

In the countryside Potter's men soon captured George Greene, an official in charge of

distributing state relief funds to the needy families of North Carolina soldiers. The troops

took $6,300 in North Carolina money from Greene, as well as his horse, saddle, bridle, and

even his pocket knife.19

On the way to Greenville, Potter's men overran a small Confederate picket station at a

place called "Four Corners," or "The Chapel." These pickets were from Capt. C. A. White's

company of Maj. John H. Whitford's Battalion (First Battalion, North Carolina Local Defense

Troops). The Union troops captured about fifteen Confederates, including one man who was

shot through the thigh while trying to escape. Before riding on to Greenville, the Yankees

paroled their Confederate prisoners and burned the pickets' tents and equipment.20

At two in the afternoon Potter's troops rode into Greenville, which the general noted in

his report was "completely surrounded by a strong line of entrenchments, but there were no

troops, excepting a few convalescents and sick in hospital."21 The raiders quickly

took possession of the town. One group of soldiers seized the post office and the courthouse.

Another group went to the jail, where they reportedly released "25 negroes . . . who had been

imprisoned in attempting to get inside our lines, in order to join the colored regiment at

Newbern."22

Southern accounts record much looting in Greenville on the raid. One observer alleged that

the "enemy . . . gutted the place, taking twenty-eight hundred ($2,800) from Dr. Blow, and

fifty-five hundred ($5,500) in bank notes from Alfred Forbes-destroyed the Commissary and

Quartermaster stores, took the earrings and breastpins off the persons of ladies and the

watches off of the gentlemen.23 A local historian pointed out another aspect

of the raid

16. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), pages 965-966.

17. Herbert Arthur Cooley to his father, July 26, 1863, H. A. Cooley Papers.

18. Alfred Holcombe to his brother, July 21, 1863, Civil War Miscellaneous Collection,

U.S. Army Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, Pa.

19. Western Democrat (Charlotte), July 28, 1863. Later that day General Potter's men

released Greene.

20. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 965;

Louis H. Manarin and Weymouth T. Jordan Jr., comps.,

North Carolina Troops 1861-1865: A Roster, 13 vols. to date

(Raleigh: Division of Archives and History, Department of Cultural Resources, 1966-),

3:84. Henry T. King, Sketches of Pitt County: A Brief History of the County, 1704-1910

(Raleigh: Edwards and Broughton, 1911), implies on page 141 that these captured men were

at Blackjack. The State Journal (Raleigh) on July 29, 1863, placed the captured picket

station at "Black-Jack Meeting House." The Daily

Progress (Raleigh), July 21, 1863, reported the raiders at Black Jack Church at 8:00 A.M.

Sunday morning.

21. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol.27 (Part 2), page 965.

22. New York Times, August 5, 1863.

23. Wilmington Journal, July 30, 1863. The same writer reported the near capture of a

black Confederate soldier. General Potter's men "found out that a free negro named

Jackson, very well known in Wilmington, and an enlisted Bugler

in Cummings' Battery, was detailed and acting in the Commissary department, and

|

| Page 7

that is not mentioned in official reports--some of the cavalrymen looted the town's saloons

and barrooms, and "many got drunk"24

About five that afternoon General Potter and his men left Greenville. They rode north

and west along the Tar River Road, which passed through the villages of Falkland and Sparta.

When the troops were crossing Tyson's Creek, just south of Falkland, some unknown Southerners

fired on the column. No one was injured, and the Southerners escaped

unseen.25 The Yankees pressed on into the night, raiding

farms and plantations along their route. In a letter to Governor Vance, Mrs. Peyton

Atkinson wrote of the Yankee raiders that "they stole all the horses they could get,

robbed persons of all their money, watches, brandy, silver, (and) arms (and) rushed

into houses at midnight, bursting open doors, into Ladies' bedrooms, whilst they were

in bed, tied citizens & locked them up in Gin houses. . . . Many a lady & her

helpless little children slept in the woods with the Green grass for their beds & the

Canopy of Heaven for their shelter."26

When the cavalry reached Sparta, just past the Pitt-Edgecombe County line, General Potter

ordered a halt and the weary men established camp. Capt. Rowland M. Hall of Company A of

the Third New York Cavalry noted that he arrived at Sparta at midnight and that his men had

been in the saddle for eighteen hours.27 At four the next

morning, Maj. Ferris Jacobs Jr. led his

six companies of the Third New York Cavalry toward Rocky Mount. Included in the detachment

was a mountain howitzer commanded by Lt. James Allis. Major Jacobs's men charged into

Rocky Mount at 8:30 A.M.28 Pvt. Andrew J. Mcintyre, a

Confederate soldier on guard duty at Rocky Mount, wrote that the Yankees "dashed up to

the depot with a shout, discharging their pistols in the air to create a panic. I had

no chance to escape, and was soon taken into custody, together with about eight or ten

other soldiers and two or three officers who were home on furlough, and about the same

number of citizens."29 The Yankees missed capturing the

southbound Wilmington mail train, which had passed through Rocky Mount at 8:00 A.M.;

however, they did seize a train that had just arrived from Tarboro carrying a few soldiers,

two carloads of ammunition, and several tons of bacon.30

Capt. Rowland Hall, of the Third New York Cavalry, described how his men captured the train.

The engineer had seen the enemy cavalrymen and had started the train's engine "& was

offered five hundred dollars for his head, and to vent their vengeance destroyed all of his

clothing, but did not succeed in capturing him." Jackson, reportedly of mixed black and

Spanish ancestry, was born in Liverpool, England. He died in Greenville in 1891, after

having served for a time as the assistant postmaster. Eastern Reflector

(Greenville), April 22, 1891.

24. King, Sketches of Pitt County, 138.

25. King, Sketches of Pitt County, 138.

26. Mrs. P. Atkinson to Zebulon B. Vance, July 28, 1863, Zebulon B. Vance, Governors

Papers, State Archives, Division of Archives and History, Raleigh.

27. Rowland M. Hall to his father, August 1, 1863, Julia Ward Stickley Papers, Private

Collections, State Archives.

28. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 968;

Herald (New York), July 27, 1863. The times

given by participants and witnesses of this raid vary widely.

29. Wilmington Journal, July 30, 1863. In 1861 at the age of nineteen, Andrew J. McIntyre, a

student from New Hanover County, had enlisted in the Eighteenth North Carolina. Wounded at

Frayser's Farm, Va., on June 30, 1862, he was able to return to his regiment during the period of

May-August, 1863.

Manarin and Jordan, North Carolina Troops, 6:408-30.

Richmond Whig, July 23, 1863.

|

| Page 8

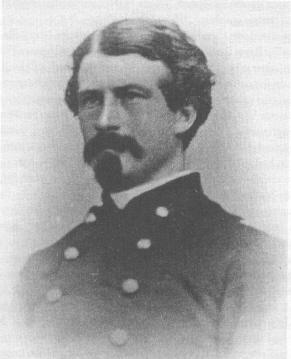

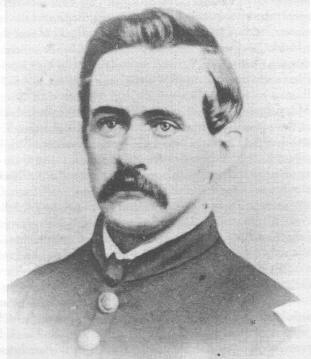

Commanding six companies of the Third New York Cavalry, Maj. Ferris Jacobs Jr. led the

portion of the raid that targeted Rocky Mount. Jacobs and his men arrived in the town

at 8:30 AM on the morning of July 20 and were responsible for widespread looting and

destruction of both private and commercial properties. Photograph from the Massachusetts

MOLLUS Collection, U.S. Army Military History Institute.

already making good headway toward the bridge . . . but Corporal [George] White of Company

A, an old railroad man from Rochester who had been purposely placed in the advance jumped

from his horse, swung himself pistol in hand upon the engine, seized the lever from the

driver & brought back the train."31 The Confederate

soldiers on the train were taken prisoner, and the conductor, Robert Watson, was robbed

by the Union troops of "$1,000 in gold and his wearing apparel.32

Captured Private Mcintyre watched Major Jacobs's men destroy the train. He later

wrote, "they run the engine off the track, and burnt the cars. While the car which was

loaded with ammunition was on fire, an explosion took place which blowed one Yankee,

who was plundering around inside, a-whizzing outside, but though badly burned, he was not

killed, and was doing well when I saw him last; and when some of his comrades expressed

sympathy with his mishap, said that was 'narthing.'"33

31. Rowland M. Hall, untitled manuscript history of the Third New York Cavalry,

J. W. Stickley Papers.

32. Daily Progress, July 23, 1863.

33. Wilmington Journal, July 30, 1863.

|

| Page 9

In addition to damaging the tracks, the Union troops set fire to the train depot, the telegraph and

ticket offices, a woodshed, a water tank, and a nearby warehouse. Spreading out from the depot,

some of the Yankees raided a nearby hotel and captured several Confederate soldiers at

breakfast. One of the men had been wounded at Gettysburg and was on his way home for a

furlough. Other raiders swept through the town, going from house to house, demanding that the

residents hand over their firearms, which they "dashed into pieces against the trees."34

Major Jacobs sent parties to attack other points outside the town. A mile north of the depot one

group of Union troops burned the railroad bridge over the Tar River. Jacobs himself led a

detachment to the Rocky Mount Mills, about a mile northwest of the depot and a short distance

west of the burning railroad bridge. The large stone mill building, a large flour mill, a thousand

barrels of flour, "immense quantities of hard-tack," and factory storerooms filled with cotton and

cloth goods were all burned. "The destruction of property," Jacobs later wrote, "was large and

complete."35 Many houses and shops in and around Rocky Mount were looted. "Nothing seems

to escape them," recorded a Charlotte newspaper. Some of the raiders "entered private dwellings,

broke open bureaus and drawers, stole clothing, petty trinkets and jewelry, in one case known to

our informant taking forcibly from a lady's finger her wedding and other rings." William E.

Pope's home was "ransacked" by soldiers who took $20,000 in cash and bonds, "his bed-clothing,

his own and family's personal clothing, including children's clothing," and even their

toothbrushes!36

W. W. Parker, who lived a short distance east of Rocky Mount, was hit hard by the raid. The

Yankees burned his stables and barns and "robbed him of money and bonds to the amount of

$70,000, destroying thirty bales of cotton belonging to him and absolutely stealing his buggy."

Private McIntyre, taken along as a prisoner, watched as the raiders "burned Mr. Parker's store,

and broke into the bar rooms and took all the liquor." The raiders also burned "three trains" of

Confederate army wagons--a total of thirty-seven wagons loaded with "all manner of stores and

supplies."37

Major Jacobs's men worked quickly and left Rocky Mount by 11:00 A.M. They rode eastward

along the River Road toward Tarboro. The raiders burned six cotton gins, several wagons, and,

according to Jacobs, over eight hundred bales of cotton at plantations along the way.38 Private

Mcintyre chatted with his captors as they rode. Some of them seem to have had a sense of

humor, as McIntyre later wrote, "the most of us (prisoners) had mules and they asked us how we

liked the cavalry service."39 At five in the morning, as Major Jacobs's detachment rode toward

Rocky Mount, the remainder of Potter's troops broke camp at Sparta and began the march

northward to Tarboro. Two companies of the Third New York Cavalry were ordered to remain at

Sparta

34. Daily Progress, July 23, 1863; New York Times, August 5, 1863; Western Democrat, July

28, 1863.

35. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 968.

36. Western Democrat, July 28, 1863.

37. State Journal, July 29, 1863; Wilmington Journal, July 30, 1863.

38. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 968.

39. Wilmington Journal, July 30, 1863.

|

Page 10

$500 REWARD.

TWO HORSES AND ONE MULE TAKEN FROM

my stables by the 3d New York Cavalry, the 30th

July, 1863, one horse, about seven years old; a sun-burnt,

yellow sorrel, thick, heavyset, short tale, with tale, and

main a little wavy; had on shoes before; hind feet white

and very tender footed, and is gentle in all work; but

rough under the saddle. The Filly is about three years

old, blood bay, with white in her forehead about the size

of a half dollar, with a long tale with a few white hairs

in the end it, and a roan spot on her side The mule

is a very small-horse mule, three years old, rather a mouse

color, with main and tail cropped, and has a dark stripe

down his back. I will pay one hundred dollars for the

Mule and two hundred dollars each for the horses, pro-

vided they are not injured. W.W. PARKER,

Aug 5-1w

Rocky Mount, N. C.

|

|

The commandeering of horses and pack animals for the Federal war effort was one of the

primary goals of the expedition. Although W. W. Parker lost more than $70,000 in cash and

securities to Union raiders, he offered to pay a $500 reward for the return of three animals taken

from his stables during the raid. This advertisement appeared in the Daily Progress (Raleigh),

August 5, 1863. to guard three bridges on the road that the Union troops would need to cross on

the return trip to New Bern.40 Meanwhile, east of Potter's men, a detachment of Confederate

cavalry hurried toward Tarboro. Brig. Gen. James G. Martin had alerted all of the region's

available Confederate troops, most of whom were concentrated at Fort Branch, near Williamston

on the Roanoke River. The Fort Branch soldiers were commanded by Lt. Col. John C. Lamb of

the Seventeenth North Carolina, who would bring two companies of his regiment, one section of

the Petersburg Artillery, and three companies of the Sixty-second Georgia Cavalry.41 At

3:00 A.M. on Monday, July 20, Maj. John T. Kennedy and his men of the Sixty-second Georgia

rode out of Fort Branch to intercept and delay Potter until Lieutenant Colonel Lamb could

assemble his foot soldiers and artillery and transport them to Tarboro. After daybreak, Kennedy

halted about four miles from Tarboro at Daniel's Schoolhouse. He sent

40. Herbert Arthur Cooley to his father, July 26, 1863, H. A. Cooley Papers.

41. State Journal, August 5, 1863. The three companies of the Sixty-second Georgia were commanded by Maj. John T.

Kennedy and had been encamped near Belvoir when they were ordered to rendezvous at Fort Branch. The individual

company commanders were Capt. W.A. Thompson and Capt. J.B. Edgerton from North Carolina, and Capt. William Ellis

from Georgia. John T. Kennedy and W. Fletcher Parker, "Seventy-fifth Regiment," in Histories of the Several Regiments

and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-65, ed. Walter Clark, 5 vols, (Raleigh:State of North Carolina,

1901)4:72-73,77.

|

| Page 11

Capt. J. B. Edgerton, an Edgecombe County man, with five soldiers to investigate the enemy's

progress. The major and the rest of his men began preparing an ambush.42 General Potter's

advance troops, led by Maj. Floyd Clarkson, galloped into Tarboro at 9:00 A.M. that morning. A

few scattered shots were fired as a handful of Confederate pickets were driven across the Tar

River bridge and out of town. Two Confederates--a lieutenant and a sergeant-were captured.43 A

Southern witness described the blue cavalry's dash into Tarboro: "some (were) armed with sabres

and carbines; most of them armed with Colt's large size pistols only. They rushed into town at a

furious rate, and picketed every approach to it as soon as possible, which was the work of only a

few minutes."44 The Union raiders quickly began their work of destruction in Tarboro. Maj.

George W. Cole took four of his companies of the Third New York Cavalry to the train depot,

where they burned a stockpile of medical supplies, "a large quantity of cotton," and

"several" railroad cars.45 Major Clarkson stated that he sent two officers with parties of men to

burn two captured steamboats, the General Hill and the Governor Morehead.46 The Yankees also

burned the partially built framework of an ironclad gunboat under construction in the shipyard

across the river from the town. The gunboat was to have been a sister ship to the ironclad,

Albemarle, which was being built on the Roanoke River. The destruction of the Tarboro gunboat

ended Confederate efforts to build an ironclad for the Tar-Pamlico region.47 From across the Tar

River, Captain Edgerton's reconnaissance party sighted the Union raiders in Tarboro. The

Confederates were not spotted until one of Edgerton's men, against orders, fired at the bluecoats.

The small band of Rebels quickly galloped back toward Daniel's Schoolhouse while the startled

Yankees organized a pursuit. The reconnaissance party had a good start and arrived at the

schoolhouse well ahead of the Union troops. Edgerton reported that a large number of enemy

cavalry had followed his men and were about two miles away. Major Kennedy ordered Edgerton

to find the Yankees, keep in sight ahead of them, and draw them toward the schoolhouse, where

he intended to ambush them.48 Major Clarkson asked Lt. Col. George Lewis if he could take

some men and attack the Rebels that had been sighted across the river. Lewis consented, and

Clarkson's detachment was soon riding toward Kennedy's trap.49 The force under Clarkson's

command consisted of Companies A, B, and F of his Twelfth New York Cavalry and a mountain

howitzer and gun crew commanded by Lt. John D. Clark of the Third New York Artillery. The

Twelfth New York Cavalry had been in North Carolina only a few weeks; and, although

Clarkson was a veteran officer, most of his men were poorly trained recruits.50

42. Kennedy and Parker, "Seventy-fifth Regiment," in Clark,

Histories of the Regiments, 4:78.

43. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 972.

44. Western Democrat, August 11, 1863.

45. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 969.

46. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 973. These steamboats had been bottled up in the Tar

River after Union forces occupied Washington in the spring of 1862. They were the only steamboats

on the Confederate-held part of the river.

47. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 29 (Part 2), page 71.

48. Kennedy and Parker, "Seventy-fifth Regiment," in Clark, Histories of the Regiments, 4:78.

49. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 972.

50. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 972. The Twelfth New York Cavalry spent most of the

winter of 1862-1863 in camp on Staten Island and received little training because of a scarcity of

horses and arms. The regiment sailed for North Carolina in May 1863. Charles McCool Snyder,

Oswego County, New York in

|

| Page 12

As Clarkson was riding out of Tarboro, Potter's men swept through the rest of the town, They

burned two large government warehouses, the jail, the market house, and several caissons and

gun carriages.51 Private establishments that were thought

to have any sort of military application

were also destroyed. Union troops burned the shop of Julius Holtzscheiter, a gunsmith,

locksmith, and a maker of surgical instruments. Also burned were the blacksmith shop of

Williams and Palamountain and a steam-powered gristmill owned by an Irish immigrant named

Michael Cohen.52 General Potter had guards posted in front

of some of the stores that lined

Tarboro's Main Street; however, many of these shops were "extensively pillaged" by Union

soldiers who slipped in through the back doors. The raiders entered a number of private homes

and took money, jewelry, watches, and other valuable items. A bitter Tarboro resident charged

that "appeals to General Potter were only answered evasively by saying to the complainant

'identify the man and I will redress you,' which was an impossibility in a crowd of licentious

soldiers straggling promiscuously. And any one who dared to charge one with a theft would have

been murdered."53

A band of the Union troops almost seized former North Carolina governor Henry T. Clark

at his

plantation home just outside of Tarboro. On the morning of the raid Clark was preparing

to start

his daily horseback ride when he spotted the approaching Yankee cavalrymen. The soldiers

sighted the former governor, and what would have been just a peaceful ride on a summer

morning became a desperate dash into the woods. Unable to catch Clark, the Union troops

returned to loot his house.54 The State Journal reported

that "Ex-Gov. Clark's residence, on the suburbs of the town, was shamefully abused.

Mrs. Clark and her niece, Miss Bettie Toole, were compelled to leave their house and take

refuge in the kitchen. They ransacked the house from top to bottom, breaking open trunks,

chests, and drawers." Much of their food was stolen, thrown down the well, or otherwise

ruined, and the raiders plundered Clark's "stock of wines and brandies."55

The Federal soldiers also raided the Branch Bank of Tarboro; fortunately, the valuables

entrusted to the bank had been taken away and hidden. The bank cashier was robbed of his

watch and clothing while the raiders searched the bank. The luckless cashier's home was

also plundered that day.56

the Civil War (Oswego, N.Y., Oswego County Historical Society and the Oswego County Civil War

Committee, 1962), 86.

51. State Journal, August 12, 1863.

52. State Journal, August 12, 1863. Michael Cohen, the owner of the Tarboro gristmill

destroyed in the raid, accompanied the Union forces back to New Bern. Without his mill

Cohen was no longer exempt from conscription. Hoping to receive compensation for his losses,

he cooperated with Union authorities in New Bern by giving them strategic information

concerning Confederate gunboats on the Tar and Roanoke Rivers. Cohen's report appears in

the Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 29 (Part 2), page 71, as well as the

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion,

Ser. I, Vol. 9, pages 164-165.

Although he was not compensated for his mill, Cohen was given a job with the Quartermaster's

Department in New Bern. North Carolina Times (New Bern), July 11, 64.

53. State Journal, August 12, 1863.

54. Western Democrat, July 28, 1863.

55. State Journal, August 5, 1863.

56. State Journal, August 12, 1863.

|

| Page 13

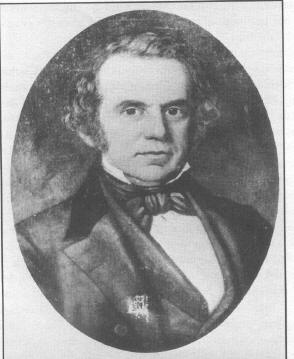

On the morning of Monday, July 20, former North Carolina governor Henry Toole Clark narrowly escaped being

captured by Federal soldiers at his plantation outside of Tarboto. Later in the day, Clark served as a volunteer firefighter,

helping to extinguish a fire that threatened to destroy the strategically important Tarboro bridge. Portrait ftom J. Kelly

Turner and Jno. L. Bridgers Jr., History of Edgecombe County, North Carolina (Raleigh: Edwards and Broughton

Printing Co., 1920), facing p. 187.

From Tarboro's Masonic lodge the raiders "carried off the fine regalia of the Chapter and all the

jewels and emblems even to the common gavil, and damaged what could not be removed."57 It

would take over a quarter of a century and a bizarre chain of circumstances before some of the

lodge's stolen property would be returned. Judge George Howard had some harrowing moments

but fared better than he had expected. Two days after the raid he quickly wrote to his wife, "the

Yankees have been here. I left and kept about an hour ahead. . . . No damage done to us. They only

took one horse and 6 or 700 segars. The Negroes behaved well--even Jane was faithful, not only

in staying, but in making such representations that they did not trouble the hotel. Only two came

into the house, and they took dinner and left."58

The anonymous Tarboro citizens who wrote accounts of Potter's Raid for Raleigh's State Journal

summed up their accounts with differing attitudes. One growled that his report was

57. State Journal, August 12, 1863.

58. George Howard to his wife, July 22, 1863, 0. Howard Papers.

|

| Page 14

merely "a partial recital of the conduct of these fiends and hyenas." Another pleaded,

"May heaven deliver our beautiful village from the painful anxieties of another such day

as Monday the 20th July, 1863."59 As these incidents were taking place in Tarboro, Major

Clarkson's New York cavalrymen were nearing Kennedy's planned ambush at Daniel's

Schoolhouse. Clarkson later wrote that he was reading directions on a guidepost when his men

were fired on by "six cavalrymen [probably Captain Edgerton's reconnaissance party] a short

distance down the road." The Southern horsemen turned and galloped away, and Clarkson

directed that Lt. John D. Clark's mountain howitzer be readied. Clarkson then ordered Capt.

Simeon Church to lead Company B of the Twelfth New York on a charge toward the band of

Rebel horsemen.60

Church's company had charged "half a mile" when Major Kennedy gave the order to fire.

Aiming their guns low--at the stirrups--the Confederates hit six Yankees and seventeen horses.

The surprised Union detachment quickly disbanded: some men dismounted, took cover, and

returned fire; others went "tilting back to Tarboro."61

Major Clarkson then ordered Lieutenant Clark to shell the Rebel position. As Clark's gun

fired, Clarkson committed the rest of his force into the fight. Company F, commanded

by Lt. Thomas Bruce, and Company A, under Capt. Cyrus Church (Simeon Church's brother),

thundered down the road to aid their Twelfth New York comrades. One participant remembered

that they charged "with a stirring yell, discharging their pistols at the Rebels . . . taking

their fire." Clarkson later wrote, "owing to the fact that it was the first time that any

of these men or officers (with the exception of five or six) had been under fire,

their horses also entirely unaccustomed to the report of firearms, very many pistols were

discharged while at 'raise pistol,' and their fire lost. "62

The Confederate fire was deadly. Company A was badly cut up and lost all three officers,

several sergeants, and numerous enlisted men. Lts. Henry A. Hubbard and Henry Ephraim Mosher,

and Sgt. John Miller were shot from their mounts.63 Capt.

Cyrus Church was also among the fallen. Confederate accounts detail two different stories

of his demise. Several weeks after the skirmish a Raleigh newspaper described what was

almost a duel between two enemy captains: "Capt.

Church was killed by Capt. [William] Ellis [of the 62nd Georgia Cavalry] . . . each firing

deliberately at the other, only a few paces apart with pistols. Several shots were exchanged

before Capt. Church fell, Capt. Ellis escaping unhurt." Another version has Major Kennedy

swinging his rifle to knock Church out of his saddle.64

59. State Journal, August 5, 1863 and August 12, 1863.

60. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 972.

61. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 972; Kennedy and Parker,

"Seventy-fifth Regiment," in Clark, Histories of the Regiments, 4:79. On page 75, mention is made of an earlier skirmish

involving Kennedy's men of the Sixty-second Georgia Cavalry, in which they were armed with

"double-barrel guns heavily charged with buck-shot." Confederate cavalrymen often carried

shotguns, rather than carbines, as Union horsemen usually carried.

62. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), pages 972-973.

63. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 973. Miller's horse

was hard to control

and had given him trouble during the raid. Gleason Wellington to his

mother, September 6, 1863, G. Wellington Correspondence.

64. State Journal, August 5, 1863; Kennedy and Parker, "Seventy-fifth Regiment,"

in Clark, Histories of the Regiments, 4:79.

|

| Page 15

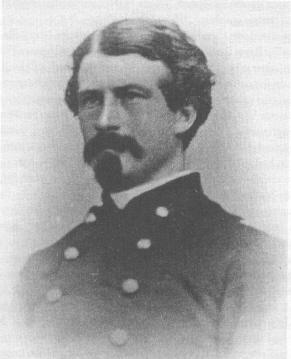

Captain Cyrus Church, commander of Company A of the Twelfth New York Cavalry, was one

of the six Union soldiers who were killed in the skirmishing at Daniel's Schoolhouse on the

afternoon of July 20. Photograph from the files of the U.S. Army Military History Institute.

Major Clarkson rallied his remaining men about a quarter of a mile from the enemy. Believing

that there were not more than forty Rebels firing on his position, he gave the order to advance.

Since most of the men's pistols were either empty or "incapable of being fired," the troops were

told to draw their sabers.65 The remnants of the three

companies of the Twelfth New York Cavalry galloped toward the woods that concealed Major

Kennedy's troops. But heavy Confederate fire from the woods turned back the Union saber

charge. Lieutenant Clark hastily moved his howitzer from its original spot, which was now

separated from the rest of Clarkson's force. Clark's horse, startled by the noise, threw him

to the ground, and two of his men were wounded. Facing certain defeat if he continued to

fight, Clarkson ordered his men to retreat back

to Tarboro.66

After the battle Major Kennedy's men captured a number of Yankees who had been cut off from

their units. The wounded bluecoats were brought to the schoolhouse, which was turned into a

makeshift hospital. Captain Church and Sergeant Miller were captured and died later that day.

Four enlisted men of the Twelfth New York Cavalry also died at Daniel's

65. The old-style Colt revolvers used black powder and were easily fouled and clogged

by powder residue.

66. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 973.

|

| Page 16

Schoolhouse,67 Eighteen of Clarkson's men, including

Lieutenants Mosher and Hubbard, were captured following the skirmish. Fourteen Union

soldiers were wounded, and one Confederate report noted that "about twenty-five" horses

were captured.68 Major Kennedy's troops were

almost unscathed at Daniel's Schoolhouse: Capt. W. A. Thompson suffered a slight wound in

one wrist, and one enlisted man was wounded.69 General Potter

ordered Maj. George Cole to take three companies of the Third New York Cavalry across the

river to help Major Clarkson. Cole's detachment crossed the bridge and traveled about a

mile eastward along the River Road. Instead of finding Clarkson, Major Cole ran into

another Rebel force--Lieutenant Colonel Lamb with Companies D and G of the Seventeenth

North Carolina and a two-gun section of the Petersburg Artillery under command of Capt.

Edward Graham. Lamb, who had left Fort Branch before dawn, held a good defensive position

about a mile from Tarboro at the junction of the River Road and the Williamston Road.

His right flank was anchored on the Tar River, and his

left was protected by a swamp.70

Major Cole recorded that his men skirmished with the Confederates for about two hours.

He sent for artillery support, and Lt. Jasper Myers of the Ordnance Corps brought a

mountain howitzer to the scene. Lieutenant Clark, who had evidently been separated from

his artillerymen and Clarkson's detachment in the fighting at Daniel's Schoolhouse, joined

Cole and took command of the gun brought up by Lieutenant

Myers.71 Capt. Thomas Norman and Company G of the

Seventeenth North Carolina went forward and partially flanked Cole's line. When the

Confederates opened fire, according to a Southern version, the Yankees "began to skedaddle and

run for the bridge protecting themselves as well as they could by the dam or levee, which runs

parallel to the river half or three-quarters of a mile."72

67. Kennedy and Parker, "Seventy-fifth Regiment," in Clark, Histories of the

Regiments, 4:80. Besides Church and

Miller, four other men, all privates from the Twelfth New York Cavalry, died at

Daniel's Schoolhouse. Pvt. Narcisse Mulway, of Montreal, Canada, was an eighteen-year-old

bugler of Bruce's Company F. Pvt. Hiram Rude of Company B, a thirty-one-year-old farmer

from Fulton, New York, left a widow and five children. Rude's youngest daughter, Lizzie,

was horn on April 29, 1863; he most likely never saw her. Pvt. David Corl, of Company A,

was a twenty-five-year-old laborer when he enlisted in Fulton, N.Y., in 1862. Also among

the dead was Company A's Pvt. William Davies, who also left a wife and several children.

After the raid a quartermaster sergeant made the routine inventory of Davies's effects. The

document listed very little, only a greatcoat, a haversack, and one "pocket book

cont[ainin]g letters." Service record files for Privates Narcisse Mulway, Hiram Rude,

David Corl, and William Davies, Twelfth Regiment New York Covalty, Compiled Service Records

of Union Soldiers Who Served During the Civil War, Record Group 94, National Archives,

Washington, D.C. See also, pension files for Privates Rude and Davies, Twelfth New York

Cavalry, Federal Pension Application Records, National Archives.

68. Muster Rolls, July-August, 1863, for Companies A, B, and F, Twelfth New York

Cavalry, Records of the Adjutant-General's Office, Record Group 94, National Archives;

Western Democrat, August 11, 1863.

69. State Journal, August 5, 1863. Pvt. William Newton McKenzie, a Georgian from Captain

Ellis's company, was recorded as "wounded in left leg in North Carolina July 21, 1863." If

the date was a day off by reason of clerical error, McKenzie could be the man wounded at

Daniel's Schoolhouse on July 20. Lillian Henderson, comp., Roster of the Confederate

Soldiers of Georgia, 6 vols. (Hapeville, Ga.: Longino & Porter, 1964), 6:304.

70. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 969; State Journal,

August 5, 1863. The noise

of the fighting at Daniel's Schoolhouse carried back to Tarboro. As he lay in an ambulance,

Sgt. Gleason Wellington heard his comrades in Company A being "all cutup." He later

wrote, "Oh how I begged for my horse and saber as I lay there burning with a

feavor when I heard the firing." Gleason Wellington to his mother,

September 6, 1863, G. Wellington Correspondence.

71. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 970.

72. Western Democrat, August 11, 1863.

|

| Page 17

Major George W. Cole led three regiments of the Third New York Cavalry across the

Tar River to assist Federal troops under the command of Maj. Floyd Clarkson who were

involved in the skirmishing at Daniel's Schoolhouse. However, Cole and his men were

intercepted by Confederate forces shortly after crossing the river and retreated back

to Tarboro after two hours of brisk fighting. Photograph from the Roger D. Hunt

Collection, U.S. Army Military History Institute.

The Confederates followed the fleeing Union troops. Captain Graham parked his two guns in a

field and fired several shells at Major Cole's detachment. Graham's shells missed the Yankees

but killed three grazing cows. Cole's men, and those of Clarkson's detachment who had escaped

the conflict at Daniel's Schoolhouse, crossed the bridge back

into Tarboro.73

General Potter thus found himself in trouble. He was deep in enemy territory and his

troops were divided at one time into five separate groups. One detachment was still at

Rocky Mount, and two companies were at Sparta. Potter's core force was established in

Tarboro, and the separate units of Major Clarkson and Major Cole were under heavy attack

in the countryside. Potter quickly reassembled his scattered forces. The Union troops

began leaving Tarboro between four and five o'clock in the afternoon of Monday, July 20.

To delay Confederate pursuit, they set the Tarboro bridge on fire shortly after

the men under

73. State Journal, August 5, 1863.

|

| Page 18

command of Majors Clarkson and Cole had crossed the river. Cole stayed in Tarboro

for a time to prevent the townspeople from putting out the fire on the

bridge.74 When Major Jacobs and his men rode into

Tarboro from Rocky Mount the entire Union force except for Major Cole's rear

guard had already started for New Bern. Having heard that Jacobs was coming, Cole

reportedly stayed behind to wait for him. Jacobs's men burned two warehouses and the

ticket agent's office as they passed by the railroad depot on their way into

town.75

Meanwhile, Major Kennedy's cavalrymen had reached the Tarboro bridge. Part of the

bridge had been torn up, and the section on the Tarboro side was burning. The townspeople

were rallied together to help fight the blaze, and former governor Clark was among the

volunteer firefighters. By 8:00 PM. the fire was out and the bridge was hastily repaired

to allow the cavalry to cross the river. However, Major Kennedy was denied permission

to continue pursuit of Potter's force until the next day. 76

The Yankees rode as far as Sparta without incident. While passing through the plantation of

Charles Vine, about a mile south of Sparta, General Potter's advance troops were attacked by

about twenty men from the Seventh Confederate Cavalry. After killing only two Union cavalry

horses, the Rebel horsemen turned and galloped down the road toward Falkland. Potter's advance

troops followed and kept up a "running skirmish."77 Unknown

to Potter, a detachment of 150 men of the Seventh Confederate Cavalry led by Maj. Thomas

Claibourne was waiting to ambush the Union troops at the Otter Creek bridge near

Falkland.78 While the Confederate advance party

was scouting and skirmishing with Potter's troops, Major Claibourne ordered his men to destroy

the bridge over Otter Creek. He also placed under cover between fifty and one hundred

dismounted men as sharpshooters. The Confederates were in a good position to block the

Yankee force, but Major Claibourne sprung his trap prematurely when he ordered his men to fire

at first sight of the Union advance troops. The sudden fire gave General Potter ample warning

that the road was blocked. The fighting that ensued continued for an hour before Col.

William C. Claibourne, Major Claibourne's superior, arrived with reinforcements that

included the Montgomery True Blues, a four-gun battery from Alabama. The True Blues,

with larger, heavier field guns than the mountain howitzers employed by Major Claihourne,

poured their fire into the Yankee position in the

woods.79 Potter believed that Claihourne's men

were "in considerable strength" and that "their position was a very difficult

one to carry."80 He wanted an alternative to

the delay and risk involved in a protracted fight at Otter Creek.

Help came from an unexpected source. Sgt. H. A. Cooley and some of his men from the Third

New York Cavalry were exploring a road that led west into the woods. After riding about half a

mile, they stopped at a house where a local black man told them about a ford

74. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 970.

75. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 970; State Journal, August 5, 1863.

76. Kennedy and Parker, "Seventy-fifth Regiment," in Clark,

Histories of the Regiments, 4:80.

77. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 965 and page 973;

Daily Progress, August 20, 1863.

78. State Journal, July 30, 1863.

79. State Journal, July 30, 1863. General Potter and the Union soldiers refer

to this place as "Tyson's Creek," although they were, according to every Southern source,

at Otter Creek. Tyson's Creek is about a mile south of Falkland.

80. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 965.

|

| Page 19

across Otter Creek that the Confederates had left

unguarded.81 Sergeant Cooley relayed this

information to General Potter. The Union forces rode to the ford and crossed the creek. Capt.

Rowland M. Hall said that his men crossed the ford "up to our horses'" ears in water. A few

pickets were left behind to continue the skirmishing and to act as a screen for the Yankees'

escape. By 11:00 PM., General Potter and his men were reported to be at the home of Col.

Walter Newton, four miles away from Colonel Claibourne.82

"Scarcely a mile" from the ford the Union troops ran into an ambush. Three Union

artillerymen were wounded in the fight. Sergeant Cooley and his men charged with drawn

sabers through the dark woods; however, their opponents disappeared into the

forest.83 Sources from Pitt County record that a local

militia officer, Col. Walter Newton, and an individual only identified

as W. B. F. Newton fired at the Union troops a short distance from the ford

in Otter Creek. Their shots "did no damage," and the two men escaped. Later that night

some of General Potter's men set fire to Colonel Newton's house, but his slaves quickly

put out the fire.84 After "taking a very

intricate path through a plantation," the Union troops reached a "piney woods road" and began

an all-night march toward New Bern.85

"A while after midnight," Pvt. Andrew McIntyre, who had been captured at the depot in Rocky

Mount, escaped. He rode through the night and reached Wilson the next

morning.86 Also during

the night, a few of Potter's men were taken prisoner. The Raleigh Daily Progress reported that

"three Yankee stragglers, exhausted, drunk, and indifferent to their fate, were captured by

citizens" near Otter Creek.87

Back at the Otter Creek bridge, Colonel Claibourne's cannon continued firing into the woods

that had been abandoned by General Potter. A disgusted Southerner later wrote that the colonel

shelled the empty woods all night, "to the destruction of nothing except the limbs of a few

unoffending trees that couldn't retreat."88 At that point a

Confederate heroine played a role in the

events. "A patriotic and heroic young lady," named Mrs. Drake, "who resided not far from Otter

Creek bridge, hastened at the dawn of day" to warn the Confederates that the Yankees had

escaped. One writer noted that Mrs. Drake "passed through it all" as "the firing was going on and

our shot [was] hurling through the trees." Despite Mrs. Drake's warning, Colonel Claibourne

reportedly did not cease fire until 5:30 A.M. It was 9:00 A.M. before the colonel allowed any of

his men to pursue the raiders.89 At daybreak Potter's force

halted "to graze their horses and take a short rest" at Grirasley's Church, about three

and a half miles north of Snow Hill and more than fifteen miles from

81. Herbert Arthur Cooley to his father, July 26, 1863, H. A. Cooley Papers.

82. Hall, manuscript history of the Third New York Cavalry;

Daily Progress, August 20, 1863.

83. Herbert Arthur Cooley to his father, July 26, 1863, H. A. Cooley Papers.

84. King, Sketches of Pitt County, 139; Stephen E. Bradley Jr., ed., North Carolina

Confederate Militia Officers Roster, as Contained in the Adjutant-General's Officers

Roster (Wilmington, N.C.: Broadfoot Publishing Company, 1992), 44.

85. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 966.

86. Wilmington Journal, July 30, 1863.

87. Daily Progress, August 20, 1863.

88. Daily Progress, August 20, 1863.

89. Daily Progress, August 20, 1863.

|

| Page 20

Otter Creek and Colonel Claibourne.90 An angry Greene

County resident alleged that a number of "tories" (Unionists) living near Grimsley's Church

received preferential treatment from General Potter. Supposedly two horses belonging

to W. P. Grimsley were confiscated by the raiders; but,

when Mr. Grimsley explained "his position" to the general, the Yankees gave him six horses to

replace the two they had taken. The same source charged, "they told Mr. Grimsley's negroes to

stay at home, while they took care to carry off all they could get belonging to rebels."91

By this time, early on the morning of Tuesday, July 21, reports of Potter's raid were alarming

much of eastern North Carolina. Brigadier General Martin telegraphed Governor Vance that

scattered forces of Confederate troops were converging on Potter. A force from Wilson, under

command of "Col. Pool," was following the Union troops. Major Claibourne was between Sparta

and Tarboro, and Colonel Claibourne was at Falkland--together the major and colonel

commanded 350 cavalrymen and five cannons. "Maj. Saunders" was at Greenville with about

150 men and some artillery, and 600 infantrymen and six cannons had been dispatched from

Kinston to intercept the raiders.92 The closest Confederate units to Potter were two companies of

the Seventh Confederate Cavalry that were commanded by Capts. Franklin Pitt and Lycurgus

Barrett. These companies fired on the Yankees but were ineffective. Major Cole, commanding

the rear guard, later wrote that his men were "annoyed all day by the firing of a squadron of rebel

cavalry."

Twice, the Confederates were driven off by grapeshot and canister fired from one of Cole's

mountain howitzers.93 The Union forces were hemmed into a triangle of Greene County land

marked off by Big Contentnea Creek to the south and Little Contenmea Creek to the north. A

number of sources mention that July had been a month with heavy rains and that the creeks and

rivers were running high making it difficult to ford large streams. To return to the guaranteed

safety of New Bern, the Yankees would have to cross either Big Contentnea Creek at

EdwardsBridge or Little Contentnea Creek at the Scuffleton bridge.94 The bridge at Little

Contentnea Creek, near the village of Scuffleton, was along the most direct route back to Swift

Creek Village and New Bern. The first troops to arrive at the Scuffleton bridge were some of

Colonel Claibourne's Seventh Confederate Cavalry, part of Whitford's Battalion, and the

Montgomery True Blues. Dr. W. J. Blow of Greenville, "a gentleman thoroughly acquainted with

the country," was on the scene and "entreated" Colonel Claibourne to wait for General Potter at

the Scuffleton bridge. Colonel Claibourne, however, decided to move most of the men to

Edwards Bridge on Big Contentnea Creek.95

90. Wilmington Journal, July 30, August 27, 1863.

91. State Journal, August 5, 1863.

92. Wilmington Journal, August 27, 1863; G. Martin to Zebulon B. Vance,

(telegram), July 21, 1863, Zebulon B. Vance, Governor's Papers, State Archives.

93. State Journal, July 30, 1863; Daily Progress, August 20, 1863;

Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 970.

94. George Howard to his wife, July 14, 1863, 0. Howard Papers; Herbert Arthur

Cooley to his

father, July 26, 1863, H. A. Cooley Papers; Official Records (Army),

Ser. I, Vol. 29 (Part 2), page 71; Daily Progress, August 20, 1863;

State Journal, July 30, 1863.

95. Daily Progress, August 20, 1863.

|

| Page21

Colonel Claibourne left a few dozen soldiers from Whitford's Battalion at the Scuffleton bridge

with orders to burn it. Inexplicably the men only pulled up some of the floor planks. At nightfall

on Tuesday, July 21, General Potter's advance troops, under command of Major Jacobs, reached

Scuffleton, The Rebels at the bridge exchanged a few shots with the enemy, and the Union

troops lost two horses. The Confederates then scattered, but eleven of Whitford's men were

captured.96 The Yankees used fence rails to repair the bridge flooring and then crossed Little

Contentnea Creek. Although it was alleged that a soldier from Whitford's Battalion escaped and

informed Colonel Claibourne that the Union troops were crossing the creek at Scuffleton, the

colonel did not order his men to intercede.97

By the time General Potter crossed the Scuffleton bridge a large contingent of contrabands

(fugitive slaves) had joined the march in order to cross Union lines and obtain freedom. Piled

into a motley assortment of farm wagons and fine carriages or mounted on mules and horses

captured from their former masters by Potter's men, the contrabands had grown to a great

number by the time they reached Little Contentnea Creek.95 Until reaching Scuffleton, Major

Cole's men had been protecting the rear of the entire column of Union troops and contrabands.

Lt. Col. George Lewis ordered Cole to "pass the negro column" and rejoin the rest of the cavalry.

Major Cole obeyed his orders and rode forward.99

At dawn on Wednesday, July 22, far behind Potter, the rear of the contraband column was at a

plantation in southern Pitt County known as the Burney Place. There they collided with the

Fiftieth North Carolina Infantry, which was in pursuit of the Union troops. Pvt. Kinchen John

Carpenter of the Fiftieth wrote that "on reaching the Burney Place, we opened fire on the column

with a small brass cannon mounted on the back of a mule, the shock being so unexpected to the

enemy that the effect was indescribable." Another account stated that "the great cavalcade,

composed of men, women, and children, perched on wagons, carts, buggies, carriages, and

mounted on horses and mules . . . was suddenly halted by our fire upon the

bridge. . . . In the

excitement and confusion which ensued many of the vehicles were upset in attempting to turn

around in the road and many others were wrecked by the frightened horses dashing through the

woods."100

While the Fiftieth North Carolina was occupied with recapturing the fugitive slaves at

the Burney Place, the Yankees were moving closer to New Bern. In a successful effort to buy

more time for escape, Potter's men scattered some of their booty along the road. The

Confederate troops, influenced by wartime scarcities and greed, frequently stopped to help

themselves to the plunder they found. Even after the raid citizens looking for their stolen

property were held back until Colonel Claibourne's men had taken their pick of the plundered

goods. The soldiers reasoned that their regiment had "frightened the enemy, and

96. State Journal, July 30, 1863;

Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 966;

Daily Progress, August 20, 1863;

Wilmington Journal, July 30, 1863.

97. Daily Progress, August 20, 1863.

98. Kinchen John Carpenter, War Diary of Kirschen John Carpenter

(Rutherfordton, N,C.: n.p., 1955), 13.

99. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 970.

100. Carpenter, War Diary, 13; J. C. Ellingron, "Fiftieth Regiment," in Clark,

Histories of the Regiments, 3:175.

|

| Page 22

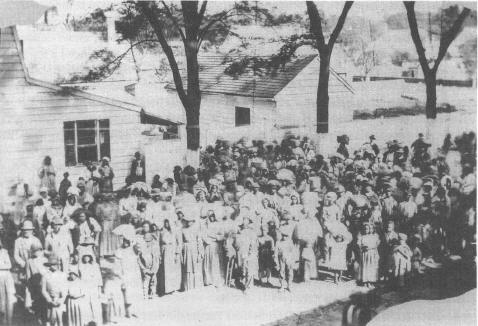

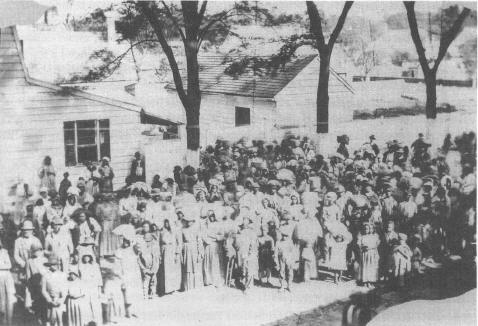

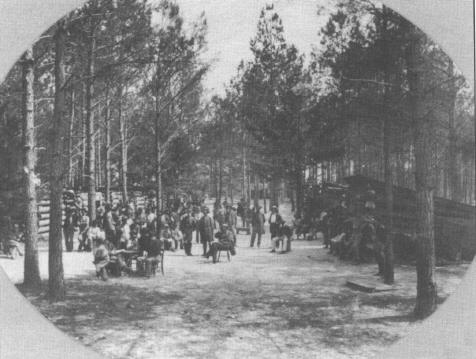

Taking advantage of the chaos caused by Potter's Raid, many slaves in the area escaped,

joined Federal troops returning to New Bern, and crossed into Union-controlled territory

and freedom. In New Bern a number of "contrabands" (fugitive slaves) found employment with

the Federal government as teamsters, laborers, craftsmen, or soldiers, Pictured here is a

group of contrabands, probably in New Bern. Photograph from the Massachusetts MOLLUS

Collection, U.S. Army Military History Institute.

the men should have whatever they wished before the owners should be allowed to assert their

rights."101

General Potter reached Swift Creek Village on the morning of Wednesday, July 22. The men

had ridden without rest since crossing the Scuffleton bridge the previous evening. After a

four-hour halt, the exhausted cavalrymen pushed themselves and their mounts for a final ride

along the road west toward Street's Ferry on the Neuse River. Street's Ferry was a

midpoint--eight miles from Swift Creek Village and eight miles upstream from New Bern, which

lay on the opposite side of the Neuse. Immediately upon his noon arrival at Street's Ferry

General Potter sent to New Bern for help.102

Shortly thereafter the Union troops were attacked by about fifty men of the

Seventh Confederate Cavalry under the command of Major Claibourne. The skirmishing

continued through the afternoon and centered around the Union mountain howitzers, which were

positioned to guard the road to Street's Ferry.103 During

one stage of the fighting Major Cole was surprised to discover that the men from part of

his right line had withdrawn from the front. The men said they had been ordered

101. Wilmington Journal, August 27, 1863.

102. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 966.

103. Wilmington Journal, September 3, 1863; State Journal, July 30, 1863.

|

| Page 23

to pull back, but Cole never gave such an order. The Opposing lines were so close together

that a creative Confederate soldier had simply shouted the order to retreat to Cole's troops.

Major Cole sent the men forward to their old position. Two Union soldiers were captured

before the fighting ceased at nightfall.104

Additional Confederate troops joined those besieging the Union forces. Major Kennedy's men

rode in from Tarboro and entered the skirmishing. About seventy men from the Fiftieth North

Carolina straggled in after dark "broken down with fatigue, heat, and hunger." Private Carpenter

thought that perhaps a quarter of his regiment arrived at Street's Ferry that evening after

marching forty-eight miles in the previous twenty-four hours. The others had fallen behind or

collapsed as a result of the oppressive July heat.105

The Confederate officers planned a morning assault on the enemy camp. These plans were

dashed at midnight when two gunboats, accompanied by a pair of steamboats carrying pontoon

bridge materials, landed at Street's Ferry. General Potter's men were safe. When word of the

Union reinforcements reached the Rebel authorities they ordered their men at Street's Ferry to

leave their campfires burning and fall back toward Kinston.106

There were at least two schools of

thought explaining the Confederate withdrawal. For Maj. John T. Kennedy it "was a blow

entirely unexpected and well calculated to vex and perplex troops who had been doing faithful

duty." On the other hand, Private Carpenter was not too upset. Reasoning that the Rebel troops

were exhausted and outnumbered, he wrote that "if the enemy had turned upon us we would

have been in a poor position for giving battle."107

The Union troops quickly began building a pontoon bridge across the Neuse River. At 7:00 A.M.

on Thursday, July 23, Potter's men and the refugee column began crossing to the south bank of

the river. By noon almost everyone was safe. Sergeant Cooley and his relieved comrades felt that

they "could now laugh at the Rebs and their pieces." When the last Union soldiers had crossed

the river, the troops dismantled the bridge and loaded bridge pieces back onto the steamboats,

along with the Confederate prisoners, the contrabands, and the

captured horses.108 As the bridge

was being taken apart a few Confederate soldiers "began to show themselves" on the north bank

of the river. On the south bank, Major Cole forbade his men to waste any ammunition on the

distant Rebels. Potter's Raid drew to a quiet finish as the

104. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 971.

105. Kennedy and Parker, "Seventy-fifth Regiment," in Clark,

Histories of the Regiments, 4:81;

Carpenter, War Diary, 13. Few casualties were reported during the

clash at Street's Ferry. There

were not enough Confederate troops to seriously threaten General Potter's 800 men,

although it

did not seem that way to the Union soldiers fighting around their embattled

mountain howitzers.

One estimate of the Rebel force at Street's Ferry listed "Major Kennedy's cavalry, about

seventy-five; Major Claibourne's cavalry, he said, about fifty; and of the 50th about 75; there

were also a few men of Whitford's Battalion." They were joined by an artillery unit, Bunting's

Battery, but even so, there could not have been many more than 300 Confederates involved in

the skirmishing. Wilmington Journal, September 3, 1863;

State Journal, July 30, 1863.

106. Kennedy and Parker, "Seventy-fifth Regiment," in Clark,

Histories of the Regiments, 4:81;

State Journal, July 30, 1863; Wilmington Journal, September 3, 1863.

107. Kennedy and Parker, "Seventy-fifth Regiment," in Clark,

Histories of the Regiments, 4:81;

Carpenter, War Diary, 13.

108. Herbert Arthur Cooley to his father, July 26, 1863, H. A. Cooley Papers;

Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 974.

|

| Page 24

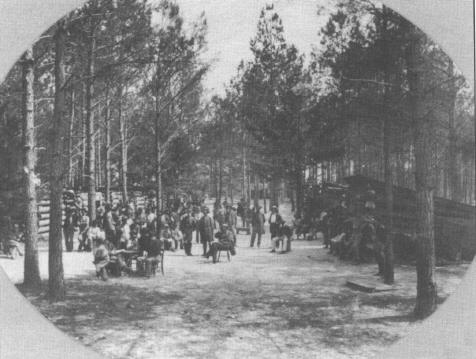

Many of the Federal troops who participated in Potter's Raid returned to Grove Camp,

near New Bern. The camp served as a base for the Third New York Cavalry and the Twenty-fifth

Massachusetts Infantry. Photograph from the Massachusetts MOLLUS Collection, U.S. Army

Military History Institute.

frustrated Confederates watched the Yankees disappear across the Neuse and head for their

camps at New Bern.109 Potter's men were weary, but proud of their achievements. Sergeant

Cooley perhaps spoke for many of his comrades when he wrote, "by noon, we were back at

Camp Grove, nearly worn out, where we got a chance to look back and see through what we had

passed and it made me shudder to think ........ six days and five nights of marching with only two

feed of oats and three days' rations for the men . . . only 8 hours sleep the whole time." Cooley

concluded his letter to his father by writing, "this I consider the greatest cavalry raid ever

made by so small a force in this war."110

Capt. Rowland M. Hall of the Third New York Cavalry lamented, "my old horse, I think, will

never recover. I had to leave him to be walked home five miles from camp. He was reeling under

me--almost all our horses are spoiled, I fear permanently." Yet Hall was pleased

109. Herbert Arthur Cooley to his father, July 26, 1863, H. A. Cooley Papers.

110. Herbert Arthur Cooley to his father, July 26, 1863, H. A. Cooley Papers. The men of the

Twelfth New York learned upon their return that their pay had been mistakenly sent to

Washington, D.C. Letter from Headquarters to Paymaster General, July 24, 1863, Regimental

Letter Book, Twelfth New York Cavalry, Records of the Adjutant-General's Office, Record Group 94,

National Archives.

|

| Page 25

with the results of the raid. "Our raid to Rocky Mount was eminently and gloriously successful,"

he wrote to his father.111 Reflecting on the raid General Potter wrote, "the behavior of the

officers and men of the command was excellent. They bore with cheerfulness the fatigue of long

marches, and the loss of food, sleep, and rest. They displayed great dash and courage in all our

encounters with the enemy."112 Potter's Raid had been

successful--the Union cavalry had inflicted great damage on important Confederate targets

in the Tar River region. Traffic on the vital Wilmington and Weldon Railroad was badly

snarled by the burning of the bridge at Rocky Mount. The Southern war effort was deprived

of badly needed rolling stock and equipment by the destruction of the engine, cars, and

railroad buildings at the Rocky Mount depot. The burning of the Governor Morehead and

the Colonel Hill ended Confederate steamboat traffic on the Tar River for the remainder

of the war. The unfinished gunboat in the Tarboro shipyard was destroyed and was to be the

last attempt to build a Confederate ironclad on the Tar River. The Rocky Mount Mills,

North Carolina's largest cotton mill, was a smoking ruin, as was a great variety of

important stockpiles of Confederate war materials and provisions. A large number of

horses and mules, scarce in the war-ravaged South, were either taken to New Bern or killed

along the way. And lastly "over 100" prisoners were brought back to New Bern, along with three

hundred newly freed slaves."113

Potter's casualties were quite low--only six Union soldiers lost their lives on the raid.

A total of seventy-five were either wounded, missing, captured, or

killed.114 General Potter later stated that

forty-three of his men were missing; except for the four who died at Daniel's Schoolhouse,

these men were presumably captured and sent to Confederate

prisons.115 Various accounts present conflicting totals

for the number of fugitive slaves recaptured by Confederate troops from the fleeing Union

column. One report claimed that more than 160 contrabands were being held in Kinston

following the raid.116 The Confederate troops captured by

Union forces during the raid were sent to prison camps in the North. The enlisted men were

paroled after a few weeks, but the four Confederate

111. Rowland M. Hall to his father, August 1, 1863, W. Stickley Papers.

112. Official Records (Army), Ser. I, Vol. 27 (Part 2), page 966. Besides pride in their

accomplishments, a small number of soldiers received more tangible rewards from the raid.